Becoming the country’s first noncommercial educational FM signal

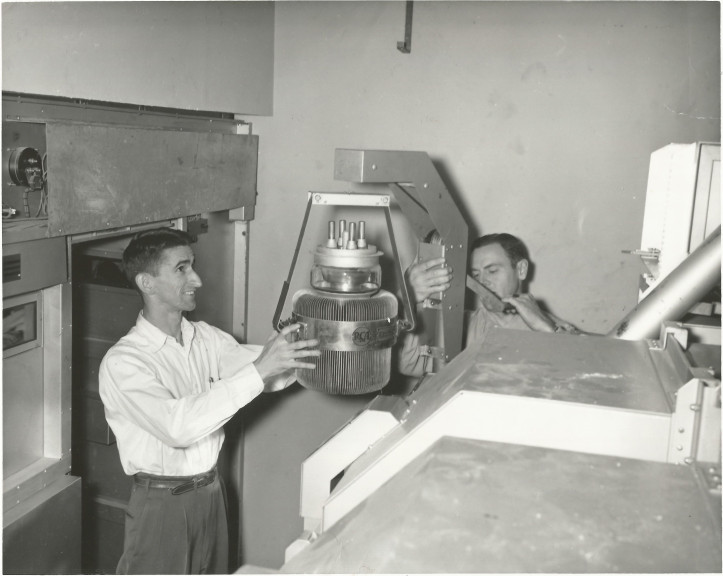

Engineers John Brugger (right) and Jim Magee prepare an FM transmitter tube at the transmitter at Allerton Park in 1955.

During this centenary year, we have delved into different aspects of WILL’s history, from the early days when WILL (then known as WRM) broadcast weekly 30-minute programs from the electrical engineering laboratory to the roles music, sports, news, children’s educational programming, and agricultural broadcasting have played in the station’s history. Though 2022 technically marks the 100th anniversary of WILL’s AM operation, this year also happens to be the 80th anniversary of WILL-FM, which has an equally interesting creation story.

In May 1940, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) authorized the creation of an FM broadcast band spanning the frequencies of 42–50 MHz. Effective January 1, 1941, there would be 40 channels available, with the first five slots reserved for noncommercial educational stations.

Jim Ebel, WILL’s chief engineer from 1937 to 1946, was excited about the high-fidelity, static-free reception that FM technology afforded. In 1941, he built an antenna in the attic of a campus auditorium so he could receive the state’s only FM station, which was owned by the Zenith Radio Company in Chicago. This proved a bit perilous and cumbersome, as anyone who wanted to join Ebel in listening to the station had to climb a ladder.

Chief Engineer Jim Ebel, center right, teaches a radio course at the University of Illinois in November 1942.

On March 18, 1941, the University of Illinois applied for a construction permit from the FCC to build an FM transmitter, which was granted on July 16, 1941. Ebel and fellow WILL engineer Ed Hamilton built WILL’s first FM transmitter based on circuit sketches from trade magazines. Over the course of the next year, Ebel and Hamilton continued to modify and relocate the antenna and transmitter.

Getting the FM station operational took some time due in no small part to America’s entrance into World War II that December. Materials for building radio receivers and transmitters were needed in the war effort, and manufacturers were compelled to accept emergency war production contracts from the US government. The FCC even halted authorizing the construction of new FM stations.

To add to the complication, WILL was in the middle of relocating after its studios on the south side of Illinois Field were deemed inadequate and a potential liability in wartime.

In February 1942, the University of Illinois’ Board of Trustees approved relocating WILL, first proposing the Lower Gymnasium of the Women’s Building (now the English Building). Given the shortage of materials needed to renovate that location, the Board decided the studios and offices should be temporarily housed in Gregory Hall. WILL moved to the second floor of Gregory Hall in March 1942. This move proved more permanent than intended, as WILL’s radio studios would remain there until the completion of Campbell Hall in 1999.

On September 30, 1942, the University of Illinois finally received its FM operating license. The FCC assigned the station the call letters WIUC. The letter “W” was assigned to all stations east of the Mississippi River (K was assigned to those stations west of it), and the “IUC” stood for either “Illinois, Urbana-Champaign” or “Illinois, University Champaign.” With this, WIUC became the first noncommercial educational FM radio station in the country and the second FM station in the state.

Following a series of test transmissions, WIUC began regular operations on November 22, 1942. WIUC’s reach was pretty small at first. Ebel and Hamilton’s 250-watt transmitter, operating on 42.9 MHz, barely reached outside Champaign-Urbana. Because WILL-AM was not allowed to broadcast after sundown due to the terms of its license, the main aim of WIUC was to extend WILL-AM’s operations to cover nighttime hours. Over the next few years, WIUC operated sporadically—usually only one night per week—and stopped broadcasting altogether for a time in 1946 while the FCC reallocated low-band FM stations to a higher band (the current 88–106 Mhz spectrum).

Jean West, seen here in 1944, was likely the first woman in charge of a transmitter as powerful as WILL's.

However, few Champaign-Urbana residents even had FM receivers at this point (reportedly only about 15–20 people). To entice listeners to buy FM receivers, transmitter engineer Jean West explained, “The station had about six small FM receivers we would loan out upon request. Sometimes we would go to people’s homes to convince them to take a receiver. We wanted people to try us. I think it did a lot of good because people did go out and buy their own receivers.

WIUC finally received its high-band frequency of 91.7 MHz and resumed operations in 1947. In April 1954, the FCC changed WIUC’s call letters to WILL-FM to reflect the station’s sister status with WILL-AM. In December 1955, WILL-FM was moved to its current frequency of 90.9 MHz, and its effective radiated power (ERP) was increased to 300 kilowatts, making it the country’s second highest powered FM station and the most powerful educational station, with an estimated service radius of 80–100 miles.

This massive increase in power was achieved through the construction of a transmitter and tower at Allerton Park just outside of Monticello. The university had bought the equipment from WTMJ in Milwaukee, where it was disassembled before being relocated and reassembled in Allerton. When WILL-FM later increased its antenna height, the FCC required it reduce its ERP to today’s 105 kilowatts.

With this increase in power, WILL-FM’s schedule expanded to 4–10 p.m. on weekdays and 1–10 p.m. on Sundays. During the daytime hours, it simulcasted WILL-AM, and at night, programming included classical music, sports, news, and other features. It wasn’t until 1974 that WILL-FM adopted the classical music format we know today.

Fun Fact: Before WILL-FM began broadcasting in stereo in 1970, WILL engineers devised an ingenious trick to simulate the stereo effect.

Men's Glee Club sing on WIUC c. 1948

They understood that stereo sound could be achieved by recording the right half of an orchestra or choir on one audio channel and the left half on another. Putting both channels on one FM signal was not yet possible, but WILL fortunately had two stations at its disposal. The engineers would record special University of Illinois School of Music events on a two-track audio recorder. The stereo tape was then played back with one channel broadcast on FM and the other on AM. Listeners were instructed how to position their AM and FM receivers to achieve the stereo effect.